.png)

.png)

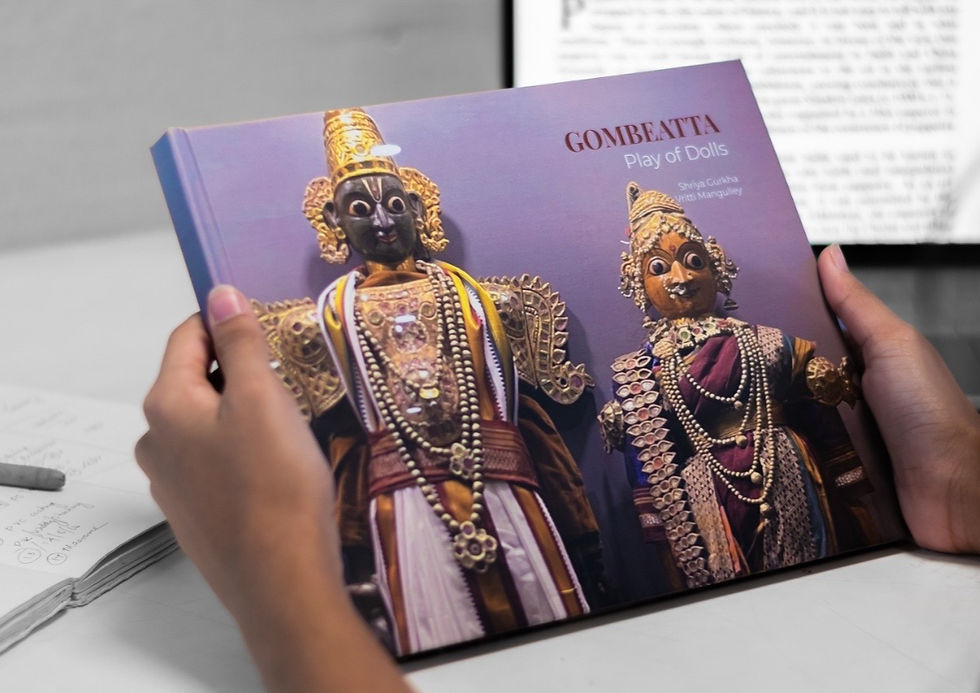

Gombeatta: A publication design aimed at addressing the economic adversities faced by a South Indian tribe, bringing design research as part of the "Tool for Social Change" initiative.

Team: Vritii Mangulley and Shriya Gurkha ( Me)

Sponsor: National Institute of Design, India

Context

This project centers on a tribe from southern India facing economic challenges due to societal biases against their work with leather, a craft often stigmatized by other communities in the region. Once celebrated in rural areas for its role in storytelling and preserving folklore and mythology, this traditional art form is now on the verge of extinction, with younger generations largely unaware of its significance.

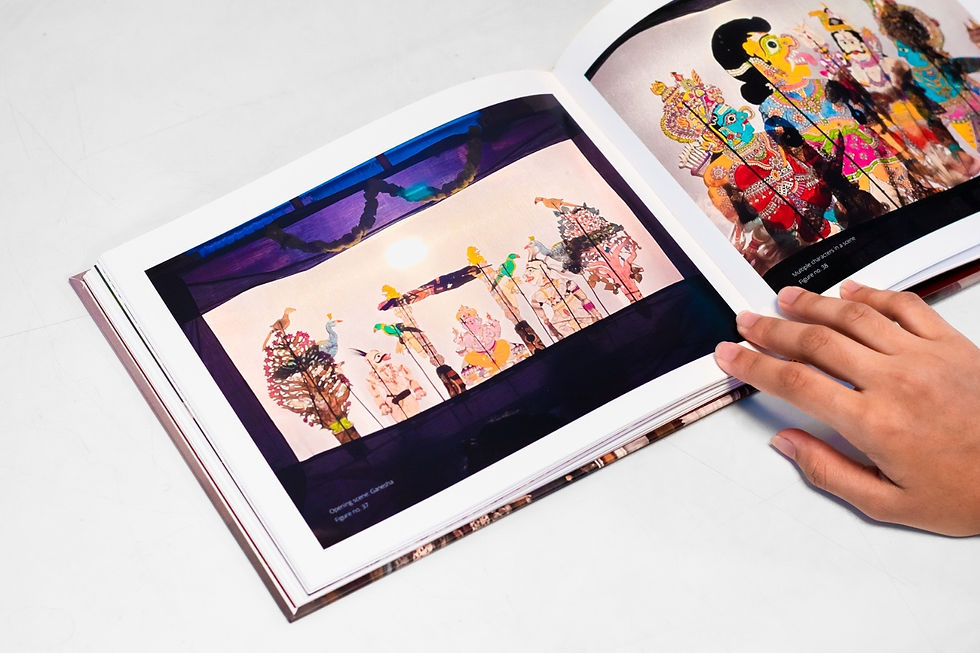

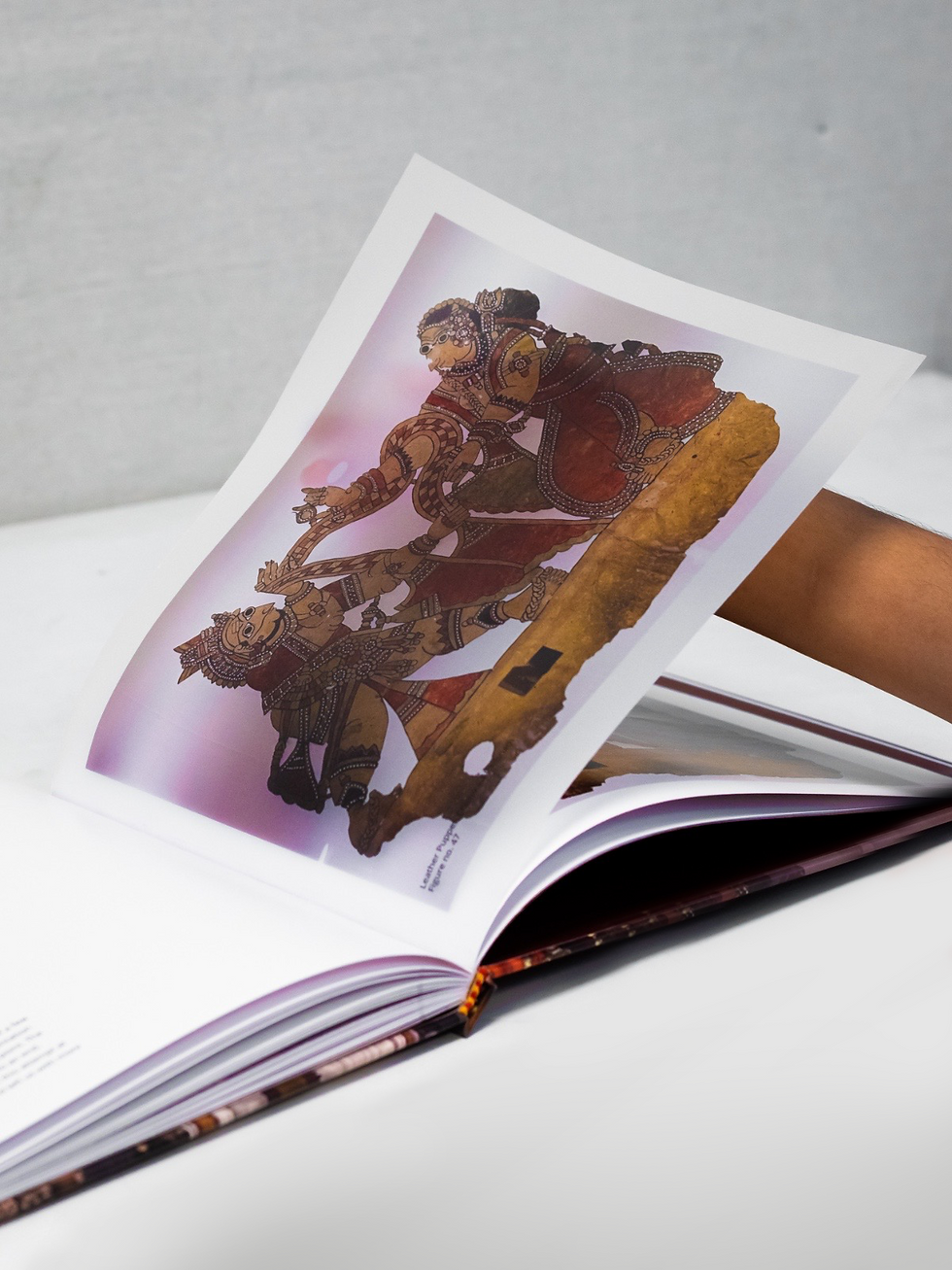

Through our publication, 'Gombeatta', we sought to promote and safeguard this cultural heritage. The initiative emphasized exploring the diverse materials used in crafting and the stories they convey, highlighting the interconnectedness between the two to foster a deeper appreciation and understanding of the craft.

How might we communicate the relationships built between materials and narratives by craftspeople ?

Methodology

Since this craft documentation required fieldwork and meetings with practitioners, we chose to adopt an ethnographic approach.

Ethnography, which originated in anthropology, is now widely used in the fields of design and social science. This approach allowed us to uncover rich narratives of cultural practices, providing insights that would not have been possible through direct interviews or straightforward questioning alone.

The process involved active interviews (conducted during fieldwork) as well as passive observation. By engaging deeply with this qualitative method, we were able to conduct an in-depth study of behaviors and interactions, gaining a nuanced understanding of the craft and its practitioners.

Participant Selection/Focus Group

For gathering primary information, our approach was to first establish online contact with various stakeholders of our research via

e-mails and contacts that were available online.

The stakeholders included - practitioners, research scientists, and curators.

Interviews

We conducted interviews with individual practitioners. The discussions were a mix of structured and unstructured interviews. We followed a method of recognising the fields and areas of discussions we wanted to have with different practitioners. Creating a general questionnaire with subdivided categories such as - History, Narrative, Technical, Visual Language, Experience and Audience.

We based a part of our questionnaire keeping in mind the insights we collected from our previous field visits. We asked them key questions that we had prepared, and let the interviewees carry forward the conversation as they saw fit. This method ensured that our main questions were answered and provided additional insights beneficial to the research.

Observation

Observational study proved to be an indispensable method in our research, primarily because the majority of our interactions with the local community were conducted in Kannada, a language we were unfamiliar with. This linguistic barrier initially posed a significant challenge; however, it became an opportunity to sharpen our focus on non-verbal communication. By observing body language, gestures, and facial expressions, we captured the emotions and intentions the craftsmen sought to convey.

This approach transcended verbal communication, enabling us to grasp cultural nuances and engage more deeply with their lived experiences. It not only enriched our understanding but also fostered empathy and a genuine connection with the community.Noticing peculiarities like layouts of spaces and Other details like local inscriptions, later proved to be significant contributors to bring out connections in the study.

Analysis

The method of analysis we maintained throughout our research included daily assessment of the respective data collected. With mediums such as audio recordings, transcripts of interviews and analysing images, we attempted to categorise our data. This allowed us to study it on a larger scale and note the interconnections that had started to emerge. This later lent a sense of cohesiveness to our research.

Learnings

Interdisciplinary Approaches

This project required merging disciplines such as anthropology, design, and storytelling. Through anthropology, we gained insights into the cultural and social context that shaped their craft traditions and practices. Design principles helped in structuring these insights into actionable and meaningful outputs, while storytelling played a vital role in preserving and conveying the essence of their experiences and heritage. By integrating these disciplines, we were able to delve into the layers of history, symbolism, and materials that defined their craft to create awareness

Collaboration

Collaborating with Vritti Mangulley significantly enhanced my ability to approach a complex and multifaceted research project. Working alongside diverse stakeholders, including researchers, curators, and Ph.D. material scientists, required a thoughtful and coordinated effort. Together, we navigated various tasks such as applying design thinking methodologies, conducting in-depth ethnographic research, and meticulously documenting our findings. This collaboration not only strengthened my research and problem-solving skills but also highlighted the value of interdisciplinary teamwork in addressing nuanced challenges and creating meaningful outcomes.